Chicago police with extremist ties have troubling records

An investigation by WBEZ, Chicago Sun-Times and the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project found allegations of excessive force, improper searches and racist comments on the job.

Key Findings

- Officials closed a probe into Chicago cops’ ties to the Oath Keepers last year without finding any wrongdoing or even investigating most of the officers linked to the group.

- Many of the cops on the Oath Keepers' rolls worked in the Special Operations Section, which was disbanded amid revelations that some members committed brazen robberies and the purported ringleader plotted to murder a colleague.

- Chicagoans recounted their experiences with the officers, offering an unprecedented look at how some of these cops have performed on the job.

- After WBEZ and the Sun-Times asked questions, Chicago police said it was opening a new investigation.

Editors’ note: The following contains graphic and offensive language.

A Chicago police officer allegedly made racist jokes at a police firing range for years, fostering a work environment that a Black colleague likened to a Ku Klux Klan gathering.

Another cop was accused of using racial slurs after pulling over a driver who mistakenly turned onto a one-way street after leaving a West Side church.

A police supervisor responded to a charity fundraising email by telling an activist from Englewood he had “no desire to help inner city poor people.”

They’re among at least 27 current and former Chicago police officials whose names appeared in leaked rosters for the Oath Keepers, an anti-government group that played a central role in the 2021 U.S. Capitol riot and counts many cops, servicemen and first responders as members.

An investigation by WBEZ, the Chicago Sun-Times and the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project found some have troubling backgrounds that include allegations of excessive force, improper searches and racist comments on the job.

At least nine of them remain on the police force, even after newly elected Mayor Brandon Johnson vowed to rid the department of extremists.

The Chicago Police Department has resisted taking action against officers for their ties with the Oath Keepers — once again placing a spotlight on a troubled disciplinary system as police leaders struggle to make sweeping, court-ordered changes to policies and practices.

Investigators closed a probe into officers’ ties to the Oath Keepers last year without finding any wrongdoing or investigating most of the police officials who appeared in the leak. The inaction drew a sharp rebuke from the city’s top watchdog, who says just joining an extremist group violates the police department’s rules of conduct.

Many of the cops on the Oath Keepers' rolls worked in the Special Operations Section, which was disbanded amid revelations that some members had committed brazen robberies and the purported ringleader plotted to murder a colleague. Some of the officers tied to the Oath Keepers have been departmental trainers, teaching young cops how to do the job.

The leaked membership records show that several cops promised to promote the Oath Keepers at work or reported that colleagues recruited them into the group.

A detective in the financial crimes section told the organization that his “brothers in Blue have passed the word amongst ourselves,” while a former sergeant vowed to “spread the word of Oath Keepers to Officers at roll calls.”

Asked recently about their involvement in the Oath Keepers, some of the officers said they had limited involvement with the group and decried its actions in Washington, D.C., on Jan. 6, 2021.

A list, a campaign pledge – and little action

The Oath Keepers’ membership data was leaked months after the group stoked the attack on the U.S. Capitol in a failed attempt to halt the transition of presidential power. Founder Stewart Rhodes and other Oath Keepers have since been convicted of sedition in what’s thought to be the broadest federal investigation in the nation’s history.

Who are the Oath Keepers?

The beginning

Stewart Rhodes started the Oath Keepers group in 2009 after America’s first Black president, Barack Obama, was elected.

Recruiting law enforcement

Rhodes is a Yale-educated lawyer and former Army paratrooper who aggressively recruited servicemen, cops and first-responders to join his crusade against what he perceived as elites trampling Americans’ rights.

Courthouse takeover

An Oath Keeper from Georgia was convicted in a 2010 plot to take over a Tennessee courthouse and detain officials after a grand jury refused to indict Obama, who the Oath Keeper claimed was not the legitimate U.S. president — the central claim of the debunked “birther” conspiracy theory.

Armed standoff

In 2014, the group’s focus shifted to an armed standoff with federal authorities at a ranch in Nevada, which raised its profile but also led to criminal charges against members of the group.

Stop the steal

The Oath Keepers backed Trump as he and his allies spent months claiming the 2020 election had been stolen.

Two days after the election, Rhodes urged other Oath Keepers to reject the results, using the same rhetoric that helped him become one of the country’s most powerful militia leaders.

January 6, 2021

Rhodes and his allies recruited members, organized paramilitary training and set up teams to shuttle guns from a Virginia hotel to the nation’s capital, though the weapons were never delivered.

The plot culminated with some followers attacking the Capitol to stop Congress from confirming President Joe Biden’s electoral victory.

Rhodes convicted

Rhodes is among the defendants who have been convicted of seditious conspiracy for orchestrating the attack.

He was sentenced in May to 18 years in prison, one of the harshest terms handed down so far in the sprawling federal probe of the insurrection. Federal prosecutors have since appealed, seeking a significantly longer sentence.

Oath Keepers’ future?

Dozens of Oath Keepers and affiliates have also been charged with federal crimes, along with members of other extremist groups like the Proud Boys and Three Percenters.

Other Oath Keepers are now cooperating with federal authorities as the group’s future hangs in the balance.

National Public Radio reported in November 2021 that a group of active Chicago cops appeared on the membership roster.

In response, the police department opened its investigation into three officers and issued a statement insisting there was “zero tolerance for hate or extremism within CPD.”

Then, in August 2022, the Anti-Defamation League sent a letter to a top police official warning that it had identified eight Chicago cops in the leaked data and providing their names.

“It is important to note that inclusion on this list means that at some point they signed up for membership,” the ADL wrote to then-First Deputy Supt. Eric Carter on Aug. 8, 2022. “The fact that a member of law enforcement joined the Oath Keepers is extremely concerning and warrants investigation.” Carter could not be reached for comment.

But the department didn’t expand the scope of its investigation after the ADL letter and the probe was closed just three months later, records show. No one was disciplined, including a Black cop who hadn’t joined the group, and police officials concluded that “memberships into organizations in itself is not a rule violation.”

However, after WBEZ and the Sun-Times obtained a copy of the ADL’s letter through an open-records request, a police spokesperson said last week the department was opening a new investigation.

The department’s past handling of extremists sparked angry City Council hearings and became an issue on the mayoral campaign trail, where Johnson promised to fire all cops “with direct ties to extremist organizations,” including the Oath Keepers.

Related stories

City Inspector General Deborah Witzburg said Johnson can and should keep that pledge, pointing to broad rules that prohibit cops from discrediting the department and undermining its goals.

“This issue goes to the soul of the police department,” Witzburg said in an interview. “We will end up with the police department we deserve through our handling of these cases.

“The fundamental question before us is whether we can abide by having members of the Chicago Police Department associate with extremist groups.”

At City Hall last week, Johnson's deputy mayor for community safety said the new administration was working to fulfill the campaign promise to fire extremist cops.

"The mayor's position remains clear — this is something that we can't stand for," Garien Gatewood said. "We want folks who want to protect folks who live here, regardless of skin color, regardless of where they're from."

Meanwhile, a new civilian-led panel is working with police officials to broaden a policy that bars officers from joining “criminal organizations,” specifically street gangs.

A draft policy submitted this year expands the scope to explicitly include groups that engage in extremist activities, including those that “seek to overthrow, destroy, or alter the form of government of the United States by unconstitutional means.”

Under the draft, police officials would compile a list of groups that would be kept from the public.

A prominent civil rights organization warns that bigotry and coded racism are ingrained in the Oath Keepers’ ideology, even though the group’s rules prohibit discrimination and some of the Chicago cops who joined come from diverse backgrounds.

“I feel like there is a direct correlation to being a member of the Oath Keepers and allegations of racist conduct,” said Jeff Tischauser, a Chicago-based senior researcher with the Southern Poverty Law Center.

The investigation by WBEZ, the Sun-Times and the OCCRP provides an unprecedented look at how cops connected to the Oath Keepers performed on the job in a city as diverse as Chicago.

‘They’re supposed to serve and protect’

Click on document icons to see specific pages referenced through the story.

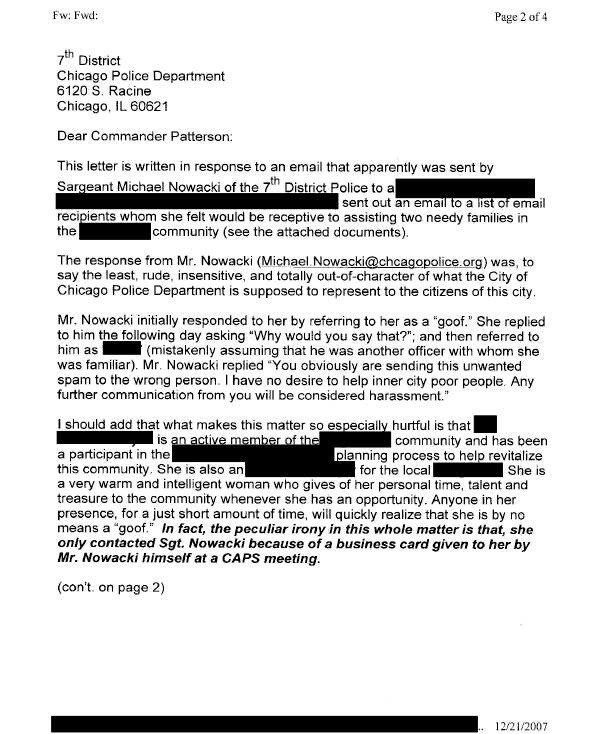

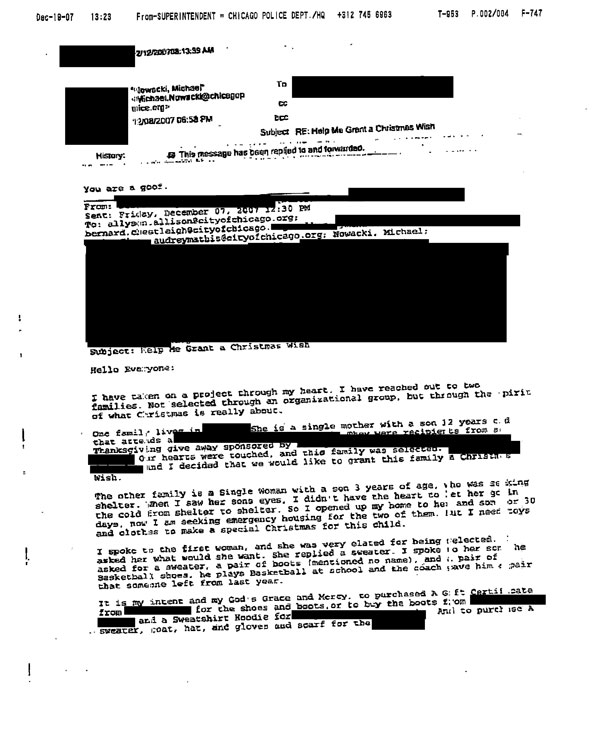

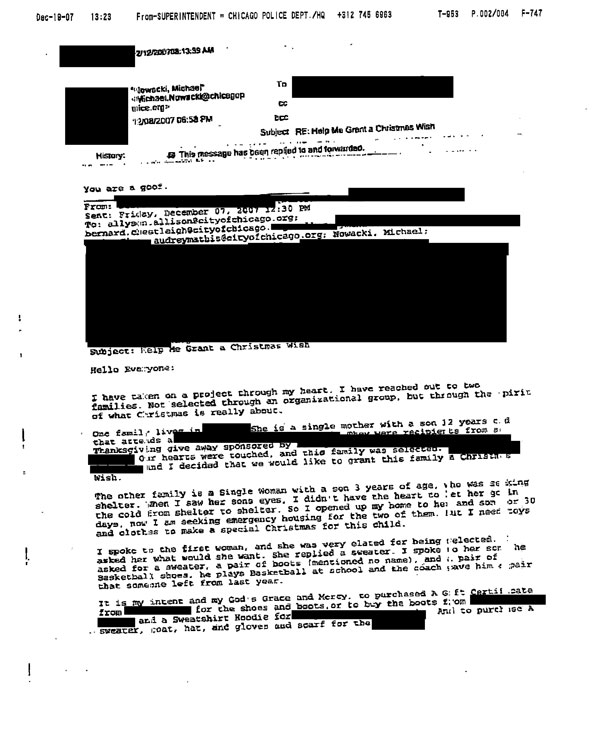

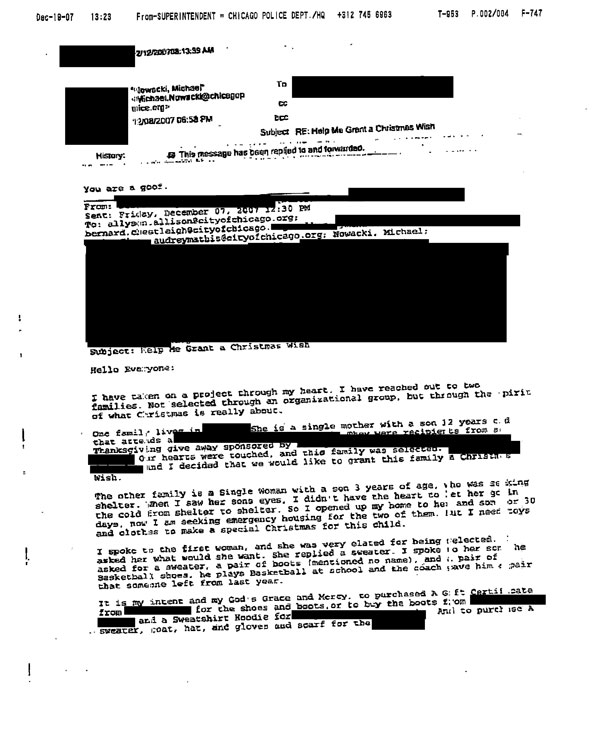

Click on document icons to see specific pages referenced through the story.Deborah Payne still becomes tearful more than 15 years after exchanging emails with a police sergeant named Michael Nowacki.

Payne, a longtime community activist on the South Side, says Nowacki — and other cops like him — are corrosive to the ties between the police department and the public, comparing them to “a leak of poison throughout the community.”

The incident that altered her previously positive view of the police came a few weeks before Christmas in 2007, when Payne was trying to help two poor families in Englewood. She sent an email to a group that included Nowacki — who had given Payne his business card at a neighborhood meeting where police try to build trust with the public.

Payne, who trained pharmacy technicians for Walgreens at the time, asked Nowacki and others for donations of clothing, food and Bibles for the families.

Using his police email account, Nowacki replied: “You are a goof.”

Nowacki also told Payne she should not have sent him the request because, “I have no desire to help inner city poor people.” He added, “Any further communication from you will be considered harassment.”

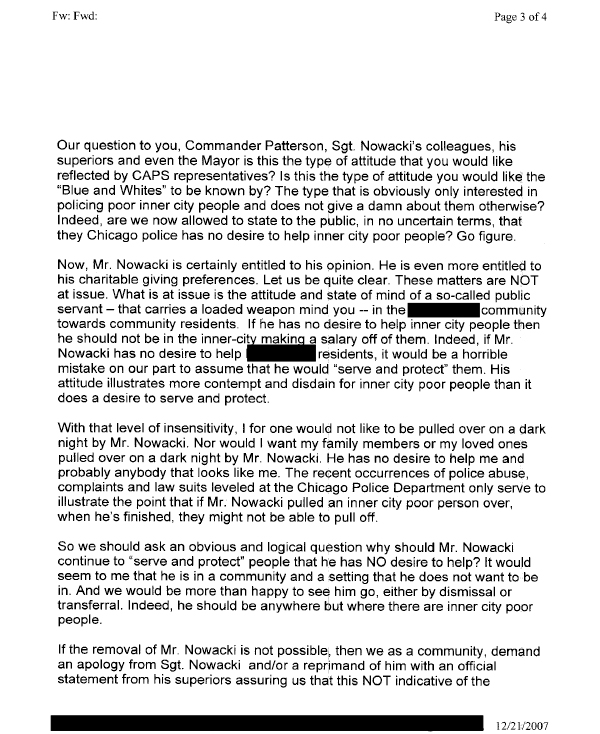

Payne called another community activist and cried as she described messages from Nowacki, according to police records obtained by WBEZ and the Sun-Times. The other activist sent a letter to the commander for Payne’s police district, saying the message from Nowacki was “rude, insensitive, and totally out of character of what the City of Chicago Police Department is supposed to represent to the citizens of this city.”

The letter to the commander said Nowacki’s response was “especially hurtful” because Payne was an active community member in efforts to improve Englewood.

The activist’s letter added that the response from Nowacki raised questions about “the attitude and the state of mind of a so-called public servant — that carries a loaded weapon mind you.” The letter writer — who, like Payne, is Black — said Nowacki “should not be in the inner city making a salary.”

Nowacki was interviewed by a Chicago police investigator about Payne’s complaint in January 2008. A veteran of the U.S. Army National Guard who served overseas, Nowacki said he was talking to the investigator "under duress."

Asked why he sent the email, Nowacki replied, “I have some issues, and I exercised some really bad judgment,” according to a transcript of the interview.

Nowacki was suspended for three days, police records show. He completed the punishment by forfeiting a fraction of the nearly 150 hours of compensatory time he had banked at that point, the records show.

Payne, 72, learned only recently from reporters that Nowacki became an Oath Keeper.

“Who’s the goof now?” Payne said she would like to tell Nowacki. “What you did, and what you’re doing, is dirty and wrong.”

She said she still works with police in her neighborhood and has not had other bad experiences with them, but thinks Nowacki should be fired.

“They're supposed to serve and protect, and their heart has that kind of venom in it,” Payne said.

Nowacki was later reprimanded for making a series of Facebook posts during the COVID-19 pandemic that criticized the police command staff, mocked an online dashboard that tracks public sentiment toward the department and showed him wearing a cloth mask.

"See, I wear my dumb mask at work," he posted.

Nowacki did not respond to requests for comment.

‘You would think you’re in the middle of a Klan rally’

Click on document icons to see specific pages referenced through the story.

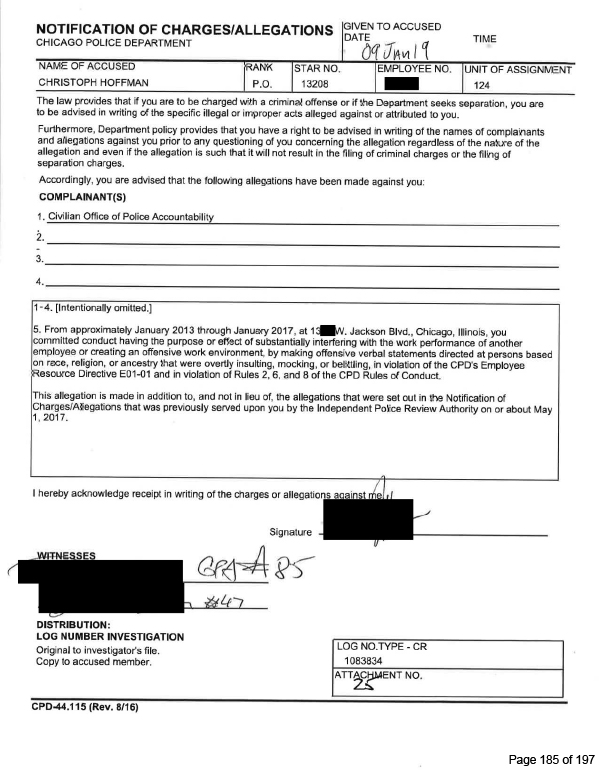

Click on document icons to see specific pages referenced through the story.After racking up complaints while serving with a notorious unit, Officer Christopher Hoffman settled into a new role training recruits on handling guns.

He eventually ran into more trouble after a Black officer accused him of making racially insensitive jokes over a four-year period that stretched until 2017, when they worked together at the police academy with at least three other cops linked to the Oath Keepers.

“I’ve been in the military in Tennessee and Alabama. I’ve never heard a person use racial comments to that extent,” the Black officer told investigators in March 2017.

The officer said he was particularly offended when Hoffman told him Water Tower Place had “food for your kind” while they were detailed downtown after the Cubs’ World Series victory in 2016, according to investigatory records.

But Hoffman had also made disparaging remarks about Jews, Asians and Puerto Ricans, according to the Black officer, who pointed to a larger cultural problem. He recalled another employee casually saying it “wouldn’t be a big problem” to call him a “n------.”

“If you were Stevie Wonder and you would come into our break room,” the Black officer said, “sometimes you would think you’re in the middle of a Klan rally.”

When confronted by investigators with the Independent Police Review Authority, Hoffman denied the allegations. IPRA closed the case without finding any wrongdoing, but he was transferred.

Hoffman previously worked alongside crooked cops in the special operations section, an elite unit that attracted some officers who effectively functioned as a robbery crew.

At least 11 cops were convicted in the scandal, including the alleged ringleader Jerome Finnigan, who was sentenced to 12 years in federal prison for plotting to kill a fellow officer he sought to silence.

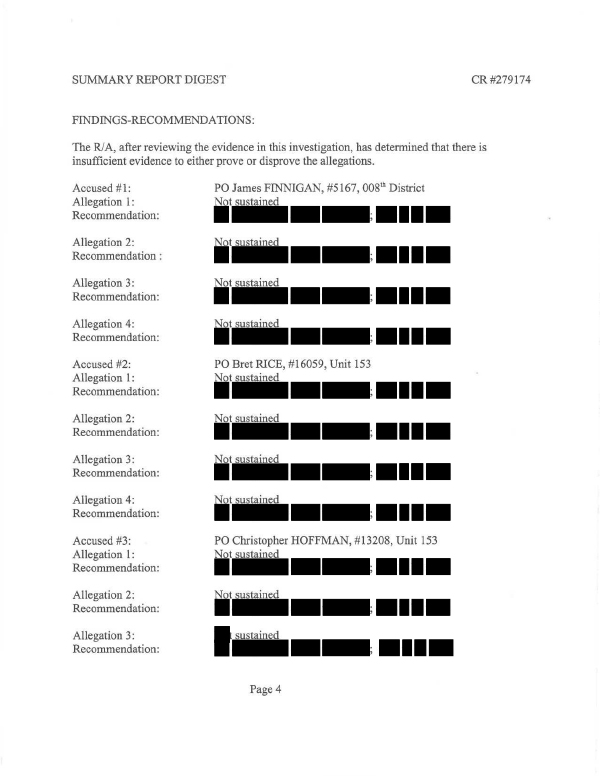

Hoffman is among nine officers — four current and five former — who were assigned to special operations and were also on Oath Keepers rolls. He was the subject of 33 investigations during his time in the unit, facing accusations of beating arrestees, conducting illegal searches and stealing cash, according to public records.

Most of his complaints were investigated by special operations sergeants, including one supervisor who resigned while facing dismissal for allegedly accepting bribes to cover up the theft of $450,000, according to public records. None of the allegations against Hoffman were sustained, including those made in six cases that targeted him and his partners for allegedly using racial slurs.

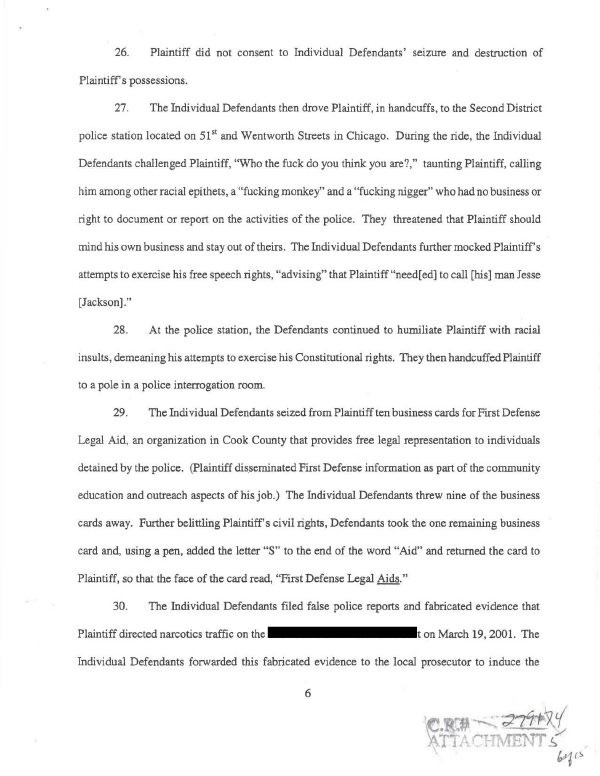

A lawsuit filed in federal court in 2002 accused Hoffman, Finnigan and others embroiled in the special operations scandal of falsely arresting a human rights worker who allegedly watched one of them strike a fleeing Black teenager with a police vehicle near the Stateway Gardens public housing complex.

The worker alleged in the lawsuit he was called a “f------ monkey” and a “f------ n-----" before he was hit with charges that were later dropped.

The city settled the suit for $10,000 without admitting any wrongdoing.

An internal police investigation found there was “insufficient evidence to either prove or disprove the allegations.”

Hoffman declined to comment for this story.

‘Scared to be around white people like that’

Click on document icons to see specific pages referenced through the story.

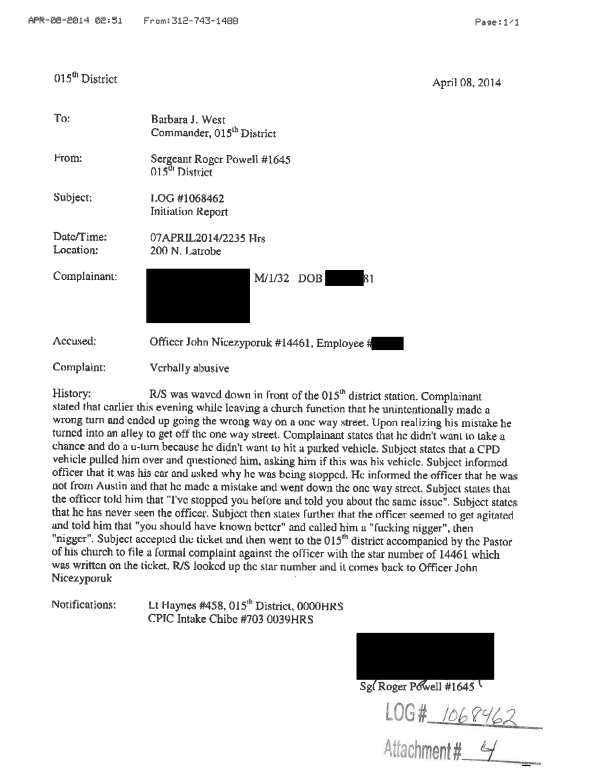

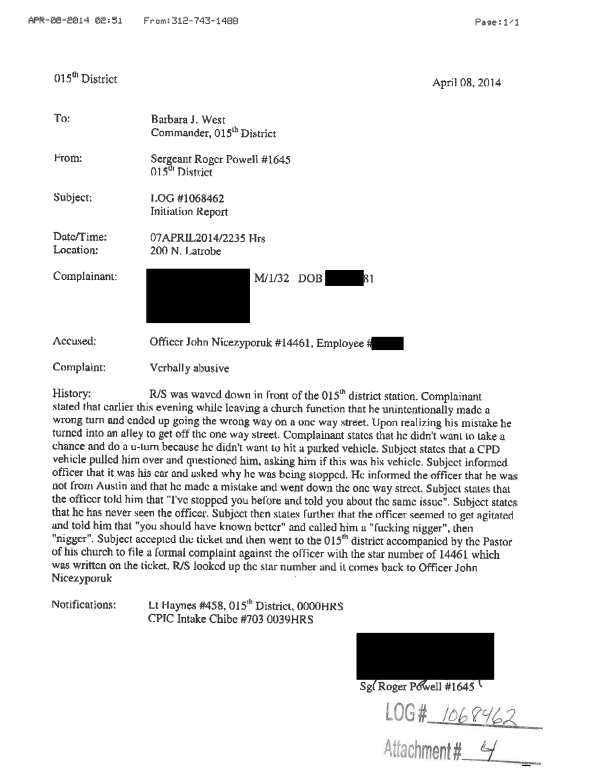

Click on document icons to see specific pages referenced through the story.Brandon Forbish, a special education teacher and football coach from the south suburbs, drove to Chicago one April night in 2014 to watch the national college basketball championship game with fellow members of Greater St. John Bible Church.

After the game, Forbish inadvertently went the wrong direction on a one-way street in Austin.

Police stopped Forbish, and one cop subjected him to a barrage of racial slurs, according to police records and a recent interview. Forbish, who is Black, alleges that a white officer named John Nicezyporuk called him multiple slurs, including a “f—--- n—--.”

Forbish filed a complaint at a police station immediately after the incident, and was interviewed by a police department investigator.

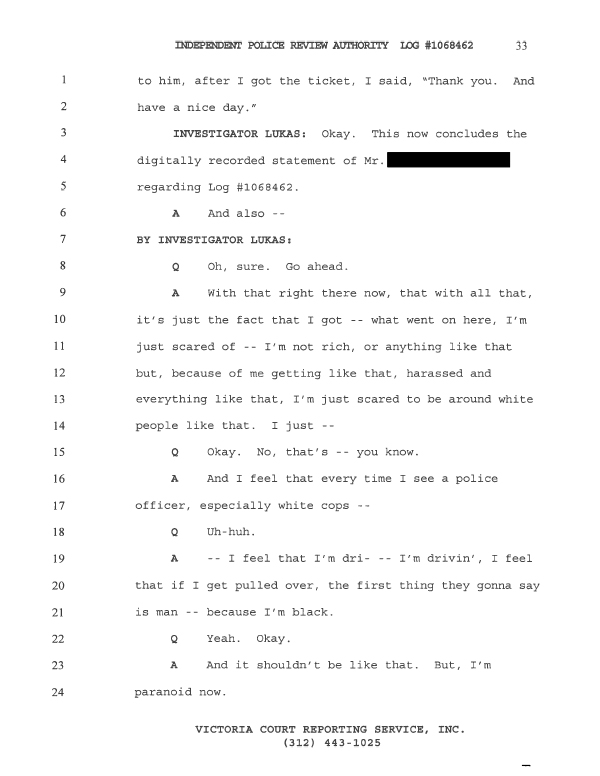

He told the police his encounter with Nicezyporuk left him “scared to be around white people like that … especially white cops.

“And it shouldn’t be like that,” Forbish said at that interview. “I’m paranoid now.”

Nicezyporuk did not respond to multiple requests for an interview.

Police records show Nicezyporuk denied Forbish’s allegations, and investigators concluded that the case against the officer was not sustained, noting, “There was no audio or video evidence.”

Forbish’s traffic ticket was eventually thrown out.

Forbish said in a recent interview that he felt “discombobulated” when told that Nicezyporuk was not disciplined. After being told that records show Nicezyporuk was among the Chicago police officers listed as belonging to the Oath Keepers, Forbish had a message for the officer.

“Man, you should be ashamed of yourself,” Forbish said. “You took an oath to serve and protect, but you’re not doing your damn job.”

Forbish’s pastor, the Rev. Ira Acree, said he remembered what happened to Forbish clearly. Forbish called Acree right after the incident and the minister accompanied Forbish to file the complaint and to his interview with the police department investigator.

Acree said the department has proven unable to police itself, and he called for an outside investigation into the Oath Keepers and other extremists on the force. He’s been among the ministers and community activists calling on Chicago police to more aggressively root out extremist cops.

“You cannot continue to allow unprofessional policing to take place, particularly in neighborhoods of color,” he said. “It’s very corrosive, and it's even more corrosive when there continues to be a pattern of this behavior.”

Records show Nicezyporuk faced another formal complaint from a Black man in 2010, who alleged the officer used racial slurs during a stop. As with Forbish’s case, Nicezyporuk denied using slurs, and the complaint was deemed not sustained by investigators.

Nicezyporuk was reprimanded, though, in 2022 after refusing to comply with the COVID-19 vaccination mandate.

“I found it to be an unlawful order, so I could not comply,” Nicezyporuk said to investigators, according to records. “This stems from just me coming onto this job 18 years ago where I took an oath, and it means something to me.

“I would not follow an order if I was ordered to violate somebody else’s civil rights, you know, a civilian on the streets, and I take offense to my rights being violated by the very department that employs me.”

‘Goofy witch hunt’

Hoffman was one of the few officers targeted in the police department’s Oath Keepers probe, but he retired in January 2022 before he could be interviewed by investigators.

Nowacki is assigned to the Shakespeare District. Nicezyporuk works in the department’s training and support group.

At least seven other active-duty cops appeared on the Oath Keepers roster:

- Officers Phillip Singto, Alberto Retamozo, and Bienvenido Acevedo are assigned to districts on the North and Northwest sides. Matthew Bracken works on the West Side.

- Officer Dennis Mack works in the public transportation section.

- Detective Anthony Keany investigates financial crimes.

- Detective Alexander Kim is assigned to the Area 3 detective division.

Bracken said in an interview for this story he has not identified with the Oath Keepers in over a decade and never attended meetings or paid membership fees, though the group’s leaked records show he’s listed as a dues-paying member in records as recently as 2015.

Bracken said he was attracted by the group’s mission statement and the fact it was for “people who served,” noting that friends in his military unit had joined and he wanted to help one of them bolster membership. Still, he called his commitment “a one-time deal.”

While Bracken said he now steers clear of politics, he referred to a news story he said exonerated some of the Oath Keepers embroiled in the Jan. 6 investigation.

“You don’t know what’s truth and what’s not,” he said of the current climate. “You can’t trust anyone anymore. There’s too many people on their own agendas.”

Acevedo said in an interview for this story that other department members pulled him into the Oath Keepers more than a decade ago, though he claimed he hadn’t “joined for any radical reasons” and only perused the group’s website, which has included incendiary content.

As a Puerto Rican from Logan Square, Acevedo said he felt alienated from the “down south kind of guys” and eventually lost interest before he even stopped being charged for dues. Although he said he regrets joining, Acevedo said his “conscience is clear.”

“I didn’t do anything wrong, other than now I’m going to be on a McCarthy-type of list,” he said. “But I didn’t go to any meetings, I didn’t go to any training. I learned more about them post-Jan. 6 than I ever did before it.”

Retamozo said in an interview that someone else signed him up around the time the Oath Keepers started in 2009, but he couldn’t recall who. While he claimed he never paid dues, records show he and Acevedo separately signed up for “full member” plans that called for monthly payments of $50 for 20 months.

Retamozo, a Navy veteran, said he was attracted to the Oath Keepers because it was for “guys that believe in the Constitution.” Now, he said he’s appalled by what the group has become.

“It’s like a slap in the face,” he said of the Oath Keepers’ role in the insurrection. “To me, it’s like we gotta stand together to protect what we’ve got left of this country.”

Anthony Keany said he’s “never been a member of the Oath Keepers” and offered alternating explanations for how he may have wound up on the rolls.

Initially, he claimed someone else signed him up to “drag down” his reputation. In the same interview, he conceded that he’d crossed paths with members of the group at a military firing range and speculated they used his information “to inflate their numbers with police and military.”

Oath Keepers membership records show he vowed to “pass the word” about the Oath Keepers to other cops, but he denied making that commitment or filling out any information. Like his colleagues, he decried the group’s role in the Capitol riot.

“Obviously it’s treason,” he said. “If you go from being a pro-Second Amendment [group] to a treasonous act, I mean, that’s horrendous. I feel bad for guys that got involved.”

The other police officials connected to the group didn’t respond to requests for comment.

John Catanzara, the president of the Chicago Fraternal Order of Police, cast the city’s efforts to root out extremism as a “goofy witch hunt,” insisting that officers should be judged by their actions and not associations that could date back years.

Catanzara said the investigations of cops linked to the far-right have gone too far, and he slammed Witzburg for repeatedly pressuring police officials to reopen cases.

Still, he expressed a willingness to purge the department of cops with “insane beliefs and practices.”

“No one’s promoting insurrection or overthrowing the government, or kidnapping like they crazily did with the plot with [Michigan Gov.] Gretchen Whitmer,” Catanzara said of the union. “But if our officers are engaged in that, then so be it. Get rid of them. We have no problem with that.”

Dan Mihalopoulos is an investigative reporter on WBEZ’s Government & Politics Team. Tom Schuba covers police for the Sun-Times. Kevin G. Hall is North America editor for the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project.

About this story

Design and development by Jesse Howe

Video and video editing by Brian Ernst

Photos throughout the series by Ashlee Rezin, Pat Nabong, Victor Hilitski, Manuel Martinez, and Anthony Vazquez

Reporters with the Chicago Sun-Times and WBEZ filed more than 200 open-records requests with the Chicago Police Department and other law enforcement agencies across Illinois. Those requests sought the personnel files for dozens of current and retired cops from the state whose names appeared in the leaked Oath Keepers membership data. Read more about how we did the investigation here.

Read the full series

How we investigated cops with ties to the Oath Keepers

October 22, 2023

Chicago police with extremist ties have troubling records

October 22, 2023

Who are the Oath Keepers?

October 22, 2023

Chicago Police Department tolerates officers with extremist ties

October 23, 2023

What Chicago police did when the Ku Klux Klan infiltrated its ranks

October 23, 2023

He was a rising football star — then he met this state trooper

October 24, 2023